Bloomsbury, Knopf, Penguin Random House

Bloomsbury, Knopf, Penguin Random HouseFrom multigenerational family sagas to speculative dystopias – the very best fiction of the year so far.

Riverhead Books, Penguin Random House

Riverhead Books, Penguin Random HouseDream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

More than 10 years have passed since Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s acclaimed Americanah, so the arrival of her new novel is a big literary moment. Dream Count is built around interconnecting storylines and the friendship of three Nigerian women whose lives have not worked out as they had envisioned. Recounting the characters’ hopes and struggles, the novel interweaves childhood and early-adult memories with the women’s current lives. It is “worth the wait,” says The Observer, and is like “four novels for the price of one, each of them powered by the simple but evergreen thrill of time spent in the company of flesh and blood characters lavishly imagined in the round.” The book explores “big themes” according to the New Statesman – masculinity, race, colonialism, power. “A complex, multi-layered beauty of a book. Extraordinary. ” (LB)

We Do Not Part by Han Kang

We Do Not Part was released in English translation in February, although it was originally published in Han Kang’s native South Korea in 2021, and therefore helped contribute to the body of work that won her the 2024 Nobel Prize for Literature. Drawing comparisons with her Booker Prize-winning bestseller, The Vegetarian, and similarly blurring the lines between dreams and reality, We Do Not Part explores the relationship between two women, Kyungha and Inseon, while uncovering a violent and forgotten chapter in Korean history. The LA Times calls We Do Not Part: “exquisite and profoundly disquieting”. It writes of Han Kang: “her singular ability to find connections between body and soul and to experiment with form and style, are what makes her one of the world’s most important writers.” (RL)

Stag Dance by Torrey Peters

The follow-up to Torrey Peters’ critically acclaimed debut Detransition, Baby is a collection of tales, each with an intriguing premise, ranging in genre from romantic to dystopian to historical. In The Masker, a young party-goer on a hedonistic Las Vegas weekend must choose between two guides, a mystery man or a veteran trans woman; in The Chaser an illicit boarding-school romance surfaces; in the titular Stag Dance a group of lumberjacks in the 19th Century, working deep in the forest, plan a winter dance – with some of the men volunteering to attend as women. The Chicago Review of Books compares the collection favourably to Peters’ debut, describing the stories as “seductive, dazzling, and history-making once again”. The Guardian is similarly effusive: “The pieces are meticulously crafted; especially Stag Dance, with its deft pacing and almost operatic denouement.” The writing is “mischievous rather than sanctimonious”, it adds, and “it is clear she is having a great deal of fun”. (LB)

Knopf, Pantheon

Knopf, PantheonTheft by Abdulrazak Gurnah

“A quietly powerful demonstration of storytelling mastery” writes The Observer of Theft, the 11th novel from the 2021 winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature. Set against the backdrop of postcolonial East Africa, situated between Zanzibar and Dar-Es Salaam, Tanzania, Theft is a coming-of-age tale exploring the inner lives of three teenagers – Karim, Badar and Fauzia – who bond despite growing up in very different circumstances. “A tightly focussed, beautifully controlled examination of friendship and betrayal,” writes The Economist, while The Wall Street Journal praises Gurnah’s “restraint”, adding: “he builds his fictional worlds cumulatively, giving equal regard to the ‘many things’ that make up experience. There are no single truths in this steady, mature novel, which may be why it feels so true as a whole.” (RL)

Universality by Natasha Brown

Natasha Brown’s celebrated 2021 debut, Assembly, was a short, precise novel and a dissection of class and race that was shortlisted for several awards. In her follow-up she examines how identity politics is cynically deployed, satirising on the way cancel culture and the worlds of publishing and journalism. The story begins with a dubious article attempting to unravel a mystery involving an illegal rave, a missing gold bar and a banker. Soon the novel moves on to the fallout from the exposé, and the knock-on effect of the people affected by the crime. “It’s all enormous, nasty fun,” says the Literary Review. “Infidelity, exploitation and hatred abound… Brown’s main purpose is to satirise and skewer the socio-economic forces that have shaped life in the UK since the late 2010s.” Universality is “very funny”, says the New Statesman. “Brown is an astute political observer, easily dismembering cancel culture and our media circus.” (LB)

The Names by Florence Knapp

Knapp’s debut novel begins in 1987, as Cora Atkin is pondering three different names for her newborn baby boy: Gordon, after her abusive doctor husband; Bear, the choice of her older daughter, Maia; or her preference, Julian. With the premise that each potential name offers a unique destiny, the narrative splits therein, revisiting its characters at seven-year intervals in a manner that recalls Sliding Doors. And despite its dark subject matter, critics have praised The Names for its upbeat, uplifting effect. The Standard writes: “Knapp’s deftly woven story is at once a big, bold experiment, a playful exercise in nominative determinism, a meditation on fate and a coming-of-age story”, while The Washington Post calls the novel: “a profound, deeply compassionate examination of domestic abuse,” which is “startlingly joyful and paced like a thriller”. (RL)

Penguin Press, Viking, Pamela Dorman Books

Penguin Press, Viking, Pamela Dorman BooksThe Emperor of Gladness by Ocean Vuong

Ocean Vuong’s second novel The Emperor of Gladness: “may well be the first millennial Great American Novel”, according to Art Review. It is: “perfectly tuned”, and “as wide in scope as it is quiet and tender”. It tells the story of Hai, a young gay man who has run away from home, and his coming of age in the rural northeast in Obama-era US. It also explores his friendship with Grazina, an elderly Lithuanian widow with dementia. Hai finds work in a fast-dining chain, and bonds with his mixed bag of new colleagues, who discover connection in their past hardships. The Emperor of Gladness is: “a fine-grained social panorama driven by the developing camaraderie of an ensemble cast bonded in precariousness and pain,” says The Observer. (LB)

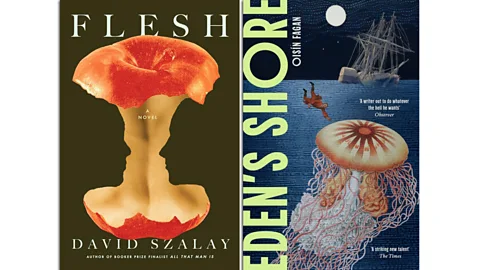

Eden’s Shore by Oisín Fagan

“A tremendous romp of a tale“, this brutal seafaring epic’s protagonist is Angel Kelly, a late-18th-Century slaver headed to Brazil with the goal to found a utopian community; chaos ensues and he washes up on the shores of an unnamed Spanish colony. With grisly attention to detail, Fagan spares little in describing the violence of the slave trade with the blackest of humour and an experimental approach to form. “Eden’s Shore is a rich and beautifully told tale of toxic adventurism” writes the TLS, while the Financial Times writes: “Alexander’s capacious performance is made to encompass the visceral, physical experiences of the journey – disease, sex, seasickness, violence – and its more cerebral aspects, in which the politics, philosophy and idealistic utopianism of the day find expression.” (RL)

Dream State by Eric Puchner

A multi-generational family saga, Dream State explores themes of love, betrayal, and the effects across generations of the choices we make. Beginning in 2004, the story is set in a rapidly warming, fictionalised version of Montana’s Flathead Valley, with the lake at the valley’s centre the nucleus of the story. Dream State traverses five decades, and: “gradually coalesces into a family history that feels monumental”, says Lit Hub. The effect is: “hypnotically telescopic, a vision of people we come to know across decades. Puchner’s manipulation of time is among his novel’s most magical elements.” His narration: “can slip from funny to harrowing as fast as young man can ski to his death”. Oprah Winfrey selected Dream State as a book club pick, describing Puchner as a “master storyteller” and the book as: “an exquisite examination of the most important relationships we have in our lives”. (LB)

Scribner, John Murray

Scribner, John MurrayThe Dream Hotel by Laila Lalami

Longlisted for the 2025 Women’s Prize for Fiction, Lalami’s fifth novel is a nightmarish speculative tale about the terrifying reaches of technology and surveillance. As Sara returns to LAX airport from a conference, she is stopped by the Risk Assessment Administration, who determine – using data from her dreams – that she is about to harm her husband. She’s transferred to a retention centre to be monitored for 21 days, where she finds – along with other dreamers – that her journey back to her family becomes more and more out of reach. “A scarily credible vision,” The Spectator writes of The Dream Hotel, continuing that it: “taps deftly into the terrors of our times”, while The Economist calls it: “a riveting tale of the risks of surrendering privacy for convenience”. (RL)

Confessions by Catherine Airey

The debut from new voice Catherine Airey has been widely praised. Confessions traces the trajectories of three generations of women as they experience the weight of the past in all its complexity. In 2001, newly orphaned by 9/11, New Yorker Cora Brady, on the cusp of adulthood, is offered a new life in Ireland – where her parents grew up – by an estranged aunt. “The narrative zips along with the crackling intelligence of Donna Tartt, full of twists and zips, and genuine surprises,” says the Irish Independent. “Confessions is an astonishing and remarkable novel and truly deserving of all the accolades coming its way.” The Guardian says: “The book is a saga: its serious pleasures are its expansiveness and range, and Airey’s rare, particular instinct for scenes or worlds that are interesting to be with, from 1970s New York art kids to early female gamers.” Confessions, it concludes, is “a cool, bold image of female pain and liberation”. (LB)

Flesh by David Szalay

Szalay’s most celebrated work, All That Man Is, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2016, explored 21st-Century manhood through the lives of nine different men. One man’s journey from teen to adulthood is the subject of Flesh. We first meet 15-year-old István in Hungary where he lives with his mother, then as he begins a relationship with a much older woman that has tragic consequences, joins the army and then rises to the top of London society. With Flesh, Szalay employs an even more pared-down version of his spare, minimalist prose to explore the meaning of a life. “Flesh is about more than just the things that go unsaid…” writes the Guardian, “it is also about what is fundamentally unsayable, the ineffable things that sit at the centre of every life, hovering beyond the reach of language.” The Observer praises Flesh’s: “searing insight into the way we live now” calling it: “a masterpiece”. (RL)